| .github/workflows | ||

| img | ||

| src | ||

| test | ||

| .gitignore | ||

| LICENSE | ||

| package.yaml | ||

| README.md | ||

| Setup.hs | ||

| stack.yaml | ||

| WhyHaskellMatters.iml | ||

Why Haskell Matters

This is a work in progress article.

Motivation

Haskell was started as an academic research language in the late 1980ies. It was never one of the most popular languages in the software industry.

So why should we concern ourselves with it?

Instead of answering this question directly I'd like to first have a closer look on the reception of Haskell in the software developers community:

A strange development over time

In a talk in 2017 on the Haskell journey since its beginnings in the 1980ies Simon Peyton Jones speaks about the rather unusual life story of Haskell.

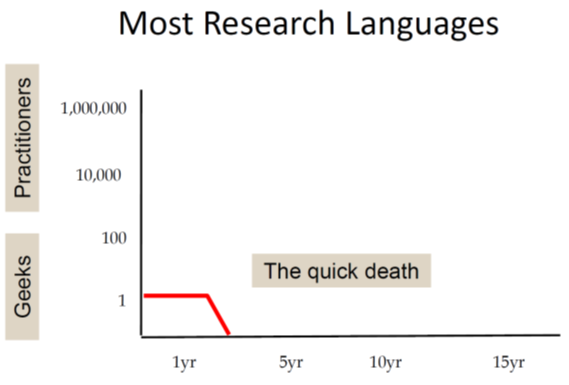

First he shows a chart representing the typical life cycle of research languages. They are often created by a single researcher (who is also the single user) and most of them will be abandoned after just a few years:

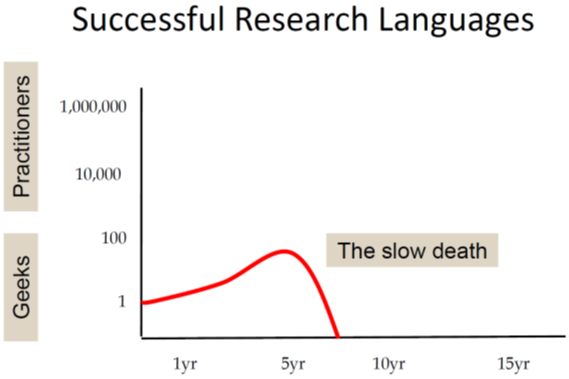

A more successful research language gains some interest in a larger community but will still not escape the ivory tower and typically will die within ten years:

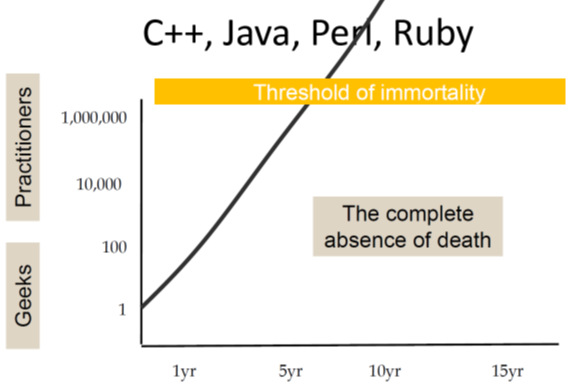

On the other hand we have popular programming languages that are quickly adopted by large numbers of users and thus reach "the threshold of immortality". That is the base of existing code will grow so large that the language will be in use for decades:

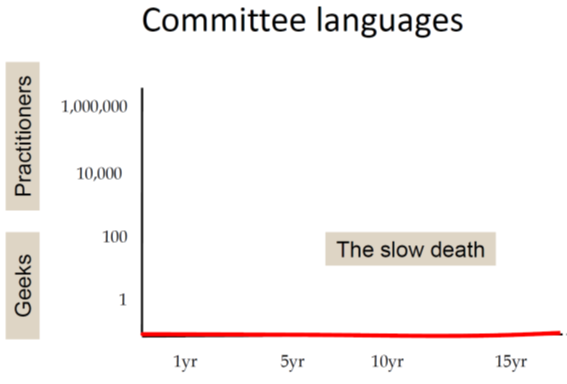

In the next chart he rather jokingly depicts the sad fate of languages designed by committees. They simply never take off:

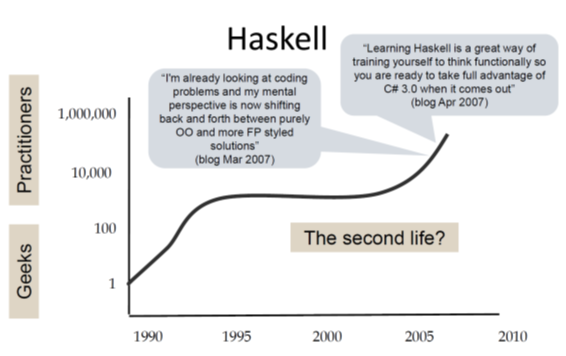

Finally he presents a chart showing the Haskell timeline:

The development shown in this chart is rather unexpected and unusual: Haskell started as a research language and was even designed by a committee; so in all probability it should have been abandoned long before the millennium!

But instead it gained some momentum in the early years followed by a rather quiet phase during the decade of OO hype (Java was released in 1995). And then again we see a continuous growth of interest since about 2005. I'm writing this in early 2020 and we still see this trend.

Being used versus being discussed

Then Simon Peyton Jones points out another interesting characteristic of the reception of Haskell in recent years. In statics that rank programming languages by actual usage Haskell is typically not under the 30 most active languages. But in statistics that instead rank programming languages by the volume of discussions on the internet Haskell typically scores much better (often in the top ten).

So why does Haskell keep to be such a hot topic in the software development community?

A very short answer might be: Haskell has a number of features that are clearly different from those of most other programming languages. Many of these features have proven to be powerful tools to solve basic problems of software development elegantly.

Therefore over time other programming languages have adopted parts of these concepts (e.g. pattern matching or type classes). In discussions about such concepts the origin from Haskell is mentioned and differences between the Haskell concepts and those of other languages are discussed. Sometimes people are encouraged to have a closer look at the source of these concepts to get a deeper understanding of their original intentions. That's why we see a growing number of developers working in Python, Typescript, Scala, Rust, C++, C# or Java starting to dive into Haskell.

A further essential point is that Haskell is still an experimental laboratory for research in areas such as compiler construction, programming language design, theorem-provers, type systems etc. So inevitably Haskell will be a topic in the discussion about these approaches.

In the next section we want to study some of the most distinguishing features of Haskell.

So what exactly are those magic powers of Haskell?

Haskell doesn't solve different problems than other languages. But it solves them differently.

-- unknown

In this section we will examine the most outstanding features of the Haskell language. I'll try to keep the learning curve moderate and so I'll start with some very basic concepts.

Nevertheless this article is not intended to be an introduction to the Haskell language (have a look at Learn You a Haskell if you are looking for an introduction).

Functions are first class citizens

Functions are first class citizens means:

- functions are nothing different from any other value. In particular this means that

- functions can be used as arguments to other functions, and

- functions can return functions as their return value.

Let's have a look how this looks like in Haskell:

-- define constant `aNumber` with a value of 42.

aNumber :: Integer

aNumber = 42

-- define constant `aString` with a value of "hello world"

aString :: String

aString = "Hello World"

In the first line we see a type signature that defines the constant aNumber to be of type Integer.

In the second line we define the value of aNumber to be 42.

In the same way we define the constant aString to be of type String.

Next we define a function square that takes an integer argument and returns the square value of the argument:

-- define a function `square` which takes an Integer as argument and compute its square

square :: Integer -> Integer

square x = x * x

Definition of a function works exactly in the same way as the definition of any other value.

The only thing special is that we declare the type to be a function type by using the -> notation.

So :: Integer -> Integer represents a function from Integer to Integer.

In the second line we define function square to compute x * x for any Integer argument x.

-

Funktionen sind 1st class citizens (higher order functions, Funktionen könen neue Funktionen erzeugen und andere Funktionen als Argumente haben)

-

Abstraktion über Resource management und Abarbeitung (=> deklarativ)

-

Immutability ("Variables do not Vary")

-

Seiteneffekte müssen in Funktions signaturen explizit gemacht werden. D.H wenn keine Seiteneffekt angegeben ist, verhindert der Compiler, dass welche auftreten ! Damit lässt sich Seiteneffektfreie Programmierung realisieren ("Purity")

-

Evaluierung in Haskell ist "non-strict" (aka "lazy"). Damit lassen sich z.B. abzählbar unendliche Mengen (z.B. alle Primzahlen) sehr elegant beschreiben. Aber auch kontrollstrukturen lassen sich so selbst bauen (super für DSLs)

-

Static and Strong typing (Es gibt kein Casting)

-

Type Inferenz. Der Compiler kann die Typ-Signaturen von Funktionen selbst ermitteln. (Eine explizite Signatur ist aber möglich und oft auch sehr hilfreich für Doku und um Klarheit über Code zu gewinnen.)

-

Polymorphie (Z.B für "operator overloading", Generische Container Datentypen, etc. auf Basis von "TypKlassen")

-

Algebraische Datentypen (Summentypen + Produkttypen) AD helfen typische Fehler, di man von OO Polymorphie kenn zu vermeiden. Sie erlauben es, Code für viele Oerationen auf Datentypen komplett automatisch vom Compiler generieren zu lassen).

-

Pattern Matching erlaubt eine sehr klare Verarbeitung von ADTs

-

Eleganz: Viele Algorithmen lassen sich sehr kompakt und nah an der Problemdomäne formulieren.

-

Data Encapsulation durch Module

-

Weniger Bugs durch

-

Purity, keine Seiteneffekte

-

Starke typisierung. Keine NPEs !

-

Hohe Abstraktion, Programme lassen sich oft wie eine deklarative Spezifikation des Algorithmus lesen

-

sehr gute Testbarkeit durch "Composobility"

-

das "ports & adapters" Beispiel: https://github.com/thma/RestaurantReservation

-

TDD / DDD

-

-

Memory Management (sehr schneller GC)

-

Modulare Programme. Es gibt ein sehr einfaches aber effektive Modul System und eine grosse Vielzahl kuratierter Bibliotheken.

("Ich habe in 5 Jahre Haskell noch nicht ein einziges Mal debuggen müssen")

-

-

Performance: keine VM, sondern sehr optimierter Maschinencode. Mit ein wenig Feinschliff lassen sich oft Geschwindigkeiten wie bei handoptimiertem C-Code erreichen.

toc for code chapters (still in german)

-

Werte

-

Funktionen

-

Listen

-

Lazyness

- List comprehension

- Eigene Kontrollstrukturen

-

Algebraische Datentypen

- Summentypen : Ampelstatus

- Produkttypen (int, int) Beispiel: Baum mit Knoten (int, Ampelstatus) dann mit map ein Ampelstatus

-

deriving (Show, Read) für einfache Serialisierung

-

Homoiconicity (Kind of)

-

Maybe Datentyp

- totale Funktionen

- Verkettung von Maybe operationen

(um die "dreadful Staircase" zu vermeiden) => Monoidal Operations

-

explizite Seiten Effekte -> IO Monade

-

TypKlassen

- Polymorphismus z.B. Num a, Eq a

- Show, Read => Homoiconicity bei Serialisierung

- Automatic deriving (Functor mit Baum Beispiel)

-

Testbarkeit

- TDD, higher order functions assembly, Typklassen dispatch (https://jproyo.github.io/posts/2019-03-17-tagless-final-haskell.html)